Democratic Degeneration: Three Easy Paths to Regression

The following is an edited transcript of the 2017 Fritz Stern Lecture, delivered on November 16 at the American Academy.

By Charles Taylor

This very pessimistic title I am going to try to explain: in a way, I appear under some kind of Gramscian slogan tonight—“pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”—because, in spite of what I have to say, I still think we’re still in with a chance, and we have to fight.

But the basic point I want to make, here at the beginning, the downer point—and I have been guilty of this myself at times—is that we have lived through an escalator analogy of history: that democracy is coming, and now it’s here, later there, and there is this kind of inevitable progress.

I think that’s not true.

Now, what shows just how untrue it is, is that our democracy contains—what is the medical term—“susceptibilities”—to axes of degeneration. I am going to talk about three, which we are very much seeing in action today, that are before us. And then I will turn, at the end, to see—this is the “optimism of the will” part—what we can do about this.

I’d like to start off by saying some very widely known things about the history of the word “democracy,” because I want then to draw from them some approaches.

Democracy, as you all know—only 200 years ago stopped being a swear word, or a nasty word. You go back to Aristotle. For Aristotle, “democracy” was the unchecked, or, as it were, uncontrolled, power of the demos. The demos being the non-elites of the society, over everyone else, including the elites, including people in aristocratic or moneyed positions—just as, oppositely, oligarchy was unchecked control by the rich and noble. So, for Aristotle, the best society was what he called politeia, a balance between the two, a balance of power.

Up until the eighteenth century, if you proposed democracy, including to the founders of the American Constitution, they would have said, “That’s not what we want at all.” They, too, thought in terms of balance, which they called the republic, which is how it translates: Plato’s politeia translates in that sense. Aristotle’s politeia, too. But democracy was really bad news. And then suddenly it becomes our word for the most desirable society. In other words, what was previously called a “polity” or “republic”—defined against democracy—becomes our word for what we are fighting to make the world safe for, or that receives our highest praise. So, we have to see in this shift, the meanings of the word. There really come to be two important applications of it, which we can see in the double meanings in the words we translate: demos, people, peuple, Volk, popolo, and so on. They always have a double meaning. On the one hand, they mean the whole population, the polity, and, on the other hand, what the Greeks the demos: the non-elites. This double meaning translates the ambition behind the word “democracy.” In the end, ideally, these two senses of the word would be fused: there would be a society ruled by the whole people, but without an elite relationship that put some in the shade, and made some disadvantaged.

Up until the eighteenth century, if you proposed democracy, including to the founders of the American Constitution, they would have said, “That’s not what we want at all.” They, too, thought in terms of balance, which they called the republic, which is how it translates: Plato’s politeia translates in that sense. Aristotle’s politeia, too. But democracy was really bad news.

So, we have certain ways of identifying democracy: we say that some countries have a democracy because they have the rule of law; they have elections in which all the people can participate—this egalitarian idea of democracy. And then we also have another judgment: “Such-and-such a country, yes, used to be a democracy, but it is not now living a fully democratic mode of life.” In this second case, we have something I would like call a “telic” concept: it’s a concept of what the ideal should be, which we never fully attain—or maybe we do, for a short time, and then we slide away again. And that gives us the key to a very important dynamic in democracy, which is part of my first point, my first path to degeneration.

There are periods in which we are moving towards democracy—liberation from foreign rule, liberation from dictatorial rule, the kind of thing that happened in 1989 in Eastern Europe, the kind of thing that happened after Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring. There’s a great sense of enthusiasm, and we are moving in the right direction. And then there a periods of lower morale, when we feel we are moving away. If you look at the 200 years of what we now call “democracy in the West,” you see that there were movements—for example the Jacksonian Revolution was a kind of democratic revolution against a class of elites, against powerful landed interests. In the nineteenth century, you have powerful vested interests; in the Gilded Age, the robber barons. After the Second World War, there was a push against that, with welfare states and social democracy, and so on. And then, since about 1975—we went sliding in the other direction. It is this important feature of democratic encouragement, enthusiasm, and moving forward, and then democratic discouragement that I would like to point out.

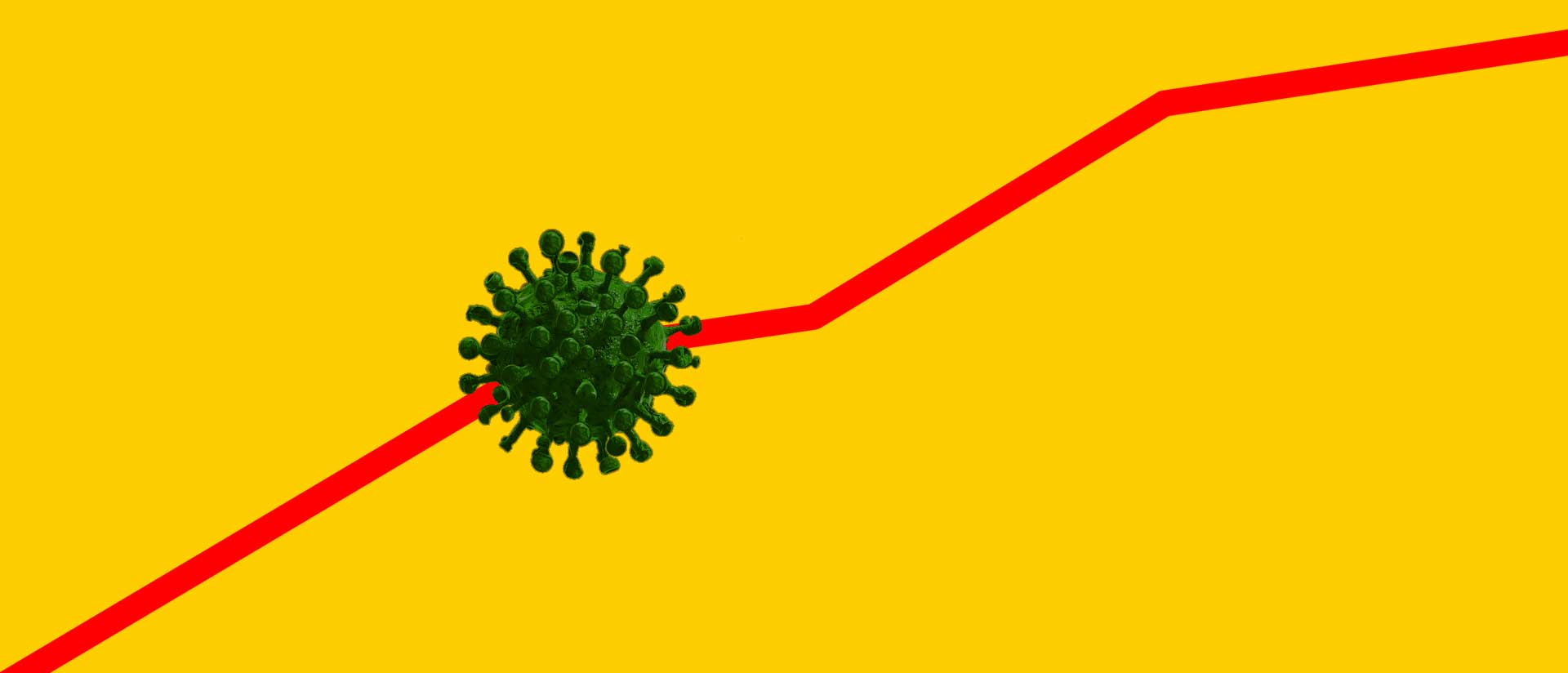

This brings me to my first kind of path of degeneration: for a variety of reasons, democracies always have to remake their move toward the telic goal. It may be because, when you move, let’s say, from the early nineteenth century to the late nineteenth century, the sources of power have changed entirely. Sources of power have changed from landed property to industrial power, to large corporations; and then they change again: finance has a tremendously important role to play in the way we live our lives. Or it may be simply because democracy may be very hard to maintain during its high tide, when it is close to its telos. But, at any case, it is clear that we have had this slide backwards since about 1975. It is translated into growing inequality, that’s the fruit of it, but it’s also the cause of it. That is why I talk about “slides,” because there is a spiraling effect: the more people feel they don’t have any real power in relation to the elites, that their fate is being decided elsewhere—whether there is going to be employment in their area, and so on and so on—the more they feel discouraged about their ability to influence this, and the less they vote. So, you see during this period I’m talking about, a decline in the levels of participation in just about all Western democracies. Some start from a higher, and some start from a lower level of democracy, but, generally speaking, the trend has been down. But, of course, that abstention increases the power of money and special interests, so the discouragement gets deeper.

There is a danger here for a spiraling downward, various kinds of downward spirals—and I don’t have time here to go fully into detail—where these kinds of movements feed on themselves.

To speak quickly about the kinds of abstentions that are taking place: they’re taking place in the West more among poor than among rich; they’re taking place more among uneducated than educated; they’re taking place more among people that have a sort of hand-to-mouth income than among those with steady income; much more among the young than the old; and much more among minorities than those in the majority.

An interesting fact in the varied world of democracy is that, in many cases, in India this is exactly the opposite: there is higher participation among the uneducated then the educated. In India, let’s hope this goes on, because we’re talking about a democracy that is a trajectory upward, the trajectory of enthusiasm, the trajectory of really believing in elections, and on the part of non-elites. But in our case, it is moving in the other direction.

What’s really worrying about this is another kind of spiral—there are many spirals, but I don’t want to go over all of them now—another kind of spiral you could call, cruelly speaking, “dumbing down.” Lots and lots and lots of people understand less and less about how things work, about what things lead to what, what voting for “x” will produce as opposed to voting for “y.” They understand much less about these mechanisms than they did in the thirty glorious years—as the French say, “les 30 glorieuses”—between 1945 of 1975, when we were building our welfare states. This is partly because the society is a little less readable: that is, if you have a big party on the Left and a big party on the Right, each with general programs, you have a pretty good idea that if you vote this way there is going to be more welfare, if you vote that way, there’s going to be less. And now there is much more fragmentation, with movements of various kinds—ecological, feminism, gay rights—so it’s less legible.

Lots and lots and lots of people understand less and less about how things work, about what things lead to what, what voting for “x” will produce as opposed to voting for “y.” They understand much less about these mechanisms than they did in the thirty glorious years—as the French say, “les 30 glorieuses”—between 1945 of 1975, when we were building our welfare states.

But there is also something very fundamental about modern democracy as against ancient democracy: there is a tendency for the thing not to be entirely legible at all, because in ancient Athens ecclesia meets, it’s dominated by the demos, it votes to do “x” or “y”—and that’s it. And it may be that they think it is a terrible thing that they have done, but it is clearly the will of the demos. But in our rule-of-law, complex, representative systems, it is often very hard to be sure if the will of the people is being listened to or not. Intrinsically, there is a tendency for this to become more opaque as it becomes less open to the non-elites’ participation. At the same time that the people don’t vote, they turn off, and they are very unclear as to what is actually happening.

That means that they are very open to various kinds of appeal, which more knowledgeable people see as totally magic thinking going on—like “I’m going to make America great again,” as an example—but that is another way in which the spiral can continue downwards. So that is one way in which democracy is susceptible to a degeneration, losing its nature—in this case, away from its implicit nature, its goal, telos. The reason I say there is a tendency is that it is self-feeding, there tends to be a self-feeding nature to this process.

The second path to degeneration I want to talk about is the one we could call the move towards or the power gained by various movement of exclusion—that is, movements that say that certain members of the polis, certain members of the republic aren’t really members of the republic. This is another basic susceptibility I think we need to look at more closely.

Democratic republics require a very definite sense of identity: Americans, Canadians, Quebecois, German, French, and so on. Why? Well, because the very nature of democracy, for several reasons, requires this strong commitment, requires participation in voting, participation in paying taxes, participation in going to war, if there is conscription. If there is to be redistribution, there has to be a very profound solidarity to motivate those modes of participation. Democracy therefore requires a strong common identity. Finally, and very importantly, if we are in a deliberative community—we are talking together, deciding among ourselves, voting, and making decisions—we have to trust that the other members of the group are really concerned with our common good.

You see a situation arising where independentist movements start very easily—and I happen to know a case like that, coming from Quebec—in which the group says, “Well when they’re talking about the good society, they’re not talking about us; they’re talking just about them. We’re not part of their horizon.” When that kind of trust breaks down, democracy is in very big trouble. It can even end up splitting into two. So we need this powerful identity.

But these powerful identities can slip very easily in a negative and exclusionary direction. Well, how? A very good book by the Yale sociologist Jeff Alexander, The Civic Code, makes this point: the common properties that make up this identity are very strongly morally charged; they’re good. As a matter of fact, in most contemporary democratic societies, there are two sides to this identity: the principles side—that we believe in representative democracy, human rights, equality—and they also have a particular side: as a Canadian, I believe in this Canadian project, or this Quebecois project, which I think are perfectly compatible—this particular project; Americans believe in this American project in realizing these values, and so on. This is what Habermas ought to have meant by “constitutional patriotism,” and I think he did.

It’s easy to see how the principles side can generate exclusion. The infamous speech by Romney in the last election—and which cost him defeat at the hands of Obama—was the “47 percent” remark: 47 percent of the people are just passengers, they are being given what they need, they are not really producing. What you have going on here is the idea that the real American is productive, enterprising, self-reliant. So, these other people are not really Americans.

You get the justification from that for a lot of things you see on the American Right—and which the Harper government in Canada tried, and we stopped them—things like vote-suppressing legislation; you have to have an identity card, which a lot of people in certain categories don’t have, otherwise you cannot come to vote. This could be a totally cynical move, but it is one that is probably justified by the sense that the people excluded fail to live up to the moral requirements of citizenship one perceives in these people.

Or, you can get another kind of exclusion: basically ethnic or historic, which provide the criteria. There are the people that really belong to the ethnicity, and then there are the people that came along later. There are the people that have always been here, and then the immigrants came. And there you get the basically ethnic coding. And here, this kind of slide can occur. Take Quebec: Je suis un Québécois. In one sense, there is a very powerful ethnic story behind that: seventy thousand French-speakers were left on the banks of the St. Lawrence when the conquest went through, in 1763, at the Treaty of Paris. And they’ve now built this magnificent French-speaking society of eight million, and so it’s been a fight for survival. It’s a very easy slide from being a Quebecois, in the sense of being a citizen of Quebec citizen today, to being what we call Quebecois de souche—old stock Quebecois.

In the United States, there are more, stranger, horrifying notions of precedent. There is a very interesting book by Arlie Hochschild, Strangers in Their Own Land, where she describes the mentality. There is a kind of order of precedence: the natives come first, the people who come from outside come second, and these liberal governments are helping all these people with second priority and not helping people with the first priority. That was a very powerful part of the Trump campaign. You get this slide.

In the United States, there are more, stranger, horrifying notions of precedent. . . . There is a kind of order of precedence: the natives come first, the people who come from outside come second, and these liberal governments are helping all these people with second priority and not helping people with the first priority. That was a very powerful part of the Trump campaign.

This slide is a catastrophe for various reasons. It’s a catastrophe because it deeply divides, hampers, and paralyzes the democratic society because it divides us into first- and second-class citizens. But it is also a catastrophe in another way, because it builds on the frustration caused by the first slide I mentioned, namely when people feel that the system is stacked against them, that they can’t affect it, and that they want to do something about it. And that something about it would be to liberate the demos or to give the demos power again, against the elites.

Only the demos has now been redescribed—either in a moralist, or ethnic, or historical-precedence way that excludes—which has the double disadvantage that it deeply divides the society, and this second disadvantage, that it does not at all meet the actual problems of these people. I’ll tell you a deep secret: Trump is not going to make America great again. I am sure you had suspicious in your mind about that, but it is going to be a double catastrophe. But you can see how these two kinds of slides can be working together, helping each other along.

The third slide, which really, in a way, follows from the second one, in this case, and the third real problem for democracy, is when it gets defined as “rule of the majority.” That means that the people who get voted against by the majority are not really part of the society any more, and we don’t want to consider the whole republic as a deliberative community, which has to work it out, respect each others’ opinions, listen to each other, find some solution. On the contrary, a certain segment of the people get ruled out. In a certain way, you get two segments ruled out by this particular kind of populism: the rejected outsiders and the elites who are supposedly favoring them.

The third real problem for democracy is when it gets defined as “rule of the majority.” That means that the people who get voted against by the majority are not really part of the society any more, and we don’t want to consider the whole republic as a deliberative community, which has to work it out, respect each others’ opinions, listen to each other, find some solution.

Now, a word about populism. There are two kinds of populism, represented both by Bernie Sanders and by Donald Trump. In one way, populism has this sense that the people are erupting into a system that is entirely run without considering them; they are breaking down the walls, breaking down the doors, disturbing business as usual—a more administratively defined action of government. But there is a very big difference between the Bernie and the Donald version: the Bernie version is truly inclusive; it’s not excluding anyone. One may not agree with the particular policies put forward; one may or may not be happy about this populist eruption, but it does not have that third and, I think, absolutely fatal feature of the Donald Trump or Marine Le Pen or Geert Wilders version, which is a deeply divisive and dead-end feature.

These three go together today. They don’t necessary always go together, but they go together today and they mutually reinforce each other today. In each case, they are something that democracy is susceptible to. It’s susceptible to sliding toward elite rule, and it’s susceptible to various mechanisms that kick in and keep it spiraling downward. It’s susceptible to “nativist”—though it is not always nativist—redefinition, and there is a certain self-feeding property about that situation also, because it starts to divide people, and it’s very hard to get them back together again. It also easily lends itself to a redefinition of democracy as pure majority rule. The idea that there is one massive majority will, and it is being frustrated by the elite and the outsiders they’re helping, and what democracy means is to establish this, no discussion, no compromise, no respect; it’s just rammed through.

And there we have the very makings of what has helped to kill democracy off in various very fragile contexts—I am thinking of Russia and Turkey, as an example. It’s built on the idea of who the real Russians and the real Turks are—their culture, orthodoxy, not being for Western liberal values or homosexuality, in the case of Russia. In the case of Turkey, it’s built on rejecting any compromise with the Kurds, et cetera. This kind of move can actually wreck a democracy, even if these were not very stable democracies to begin with, but you can still see the tendency of this direction.

I wanted to say a few words about what we can do about all this. There are also other problems I haven’t mentioned, which aggravate it: the splitting up of media so that people are in echo chambers. The echo-chamber effect is intensified by social media, the circulation thereby of total non-facts as facts, and people never have them in any way refuted, and so on—all of which makes our jobs all the harder.

What we obviously need to get out of this situation in any given country is, first of all, a program on the part of some party of reform—of the kind that Macron is trying to put together. Whether or not he succeeds, we’ll see. A program that can draw votes from both sides; on those that have always wanted to see some kind of reform in the society; on those who, in wanting some kind of reform, have been drawn off into some kind of identitarian path, because people’s identities are complex. The worker in the Rust Belt who may be attracted to Pentecostal Christianity, might not be a very great feminist, is attracted to Trump’s “I’m not politically correct”—he also wants some kind of job, or some way of educating his kids. (You might imagine figures on the American scene who might have been able to create that kind of coalition.)

Because people have these kinds of complex identities, they’re capable of entering into more than one. So we need to rebuild these boundaries crossing between these different groups. Once you do begin to build such a coalition, you begin to get a self-feeding process going in the right direction. People who never talk to each other and who see each other as strangers out there—as we Northeastern latte-sipping liberals tend to see the “rednecks” out there in West Virginia—but when you actually begin to work with people in the flesh, something very powerful happens: these senses of difference get dissolved, particularly if you have some kind of common project.

People who never talk to each other and who see each other as strangers out there—as we Northeastern latte-sipping liberals tend to see the “rednecks” out there in West Virginia—but when you actually begin to work with people in the flesh, something very powerful happens: these senses of difference get dissolved, particularly if you have some kind of common project.

We have had a lot of proof of this on the small scale. The problem is how to upscale it. The various experiments on the small scale—for example, in the States, there have been various associations between pro-life and pro-choice—that bring people together for a weekend from both sides. And then they talk to each other, and then they find out that they are not 150 miles from each other. There’s some kind of common ground, and they find that the other is not a monster. Things begin to thaw.

We did the same thing when we had big constitutional problems in Canada. Again, small scale: people brought together for a weekend—a Quebecois, an Ontarian, a BC, et cetera—and they sat around and talked. The same thing happened: all these great fears disappeared. Second, if you’re working together on something, a common project, that strengthens it, and also, you find here that you’re not only breaking down the barriers, but you’re also upping the democratic intelligence. The dumbing-down effect is countered by the fact that you’re trying to work out common projects, actually confronting the difficulties and where things have to be changed, and where the levers are. There are various attempts to do this on the small scale, three of which I recommend your looking up. A man called Luke Bretherton has written a book on this, in which he shows how they worked in London, in a very interesting way.

There’s another kind of community organization, an organization in the States, that sends out people to meet leaders in the community to get over some kind of terrible impasse in the community—full disclosure: my niece in involved in this group advising this community; she’s in the States, she’s in Boston, but she’s advising a community in northern Wisconsin, precisely who voted for Trump, because they’re in the Rust Belt, and so on, but they want to find a way out.

And then there is Patrizia Nanz, who should have been there tonight and who invited me to the IASS. She and Claus Leggewie, when she was at the Kulturwissenschaftliches Institut in Essen, wrote this very interesting book, Die Konstruktive, which I think is going to be translated into English, in which various cases where there was a large project from government, and people were not sure if they wanted to go along with it, and they didn’t know what to do about it. They brought together a sample of people who were willing to talk about it, and exchange. They came up with very interesting, alternative solutions.

So, there are various attempts on the micro-scale. And even though the micro-scale is not sufficient, it is a very important part of the whole movement. Earlier, I was talking about the macro-scale of large coalitions, but these large coalitions are successful, to some extent, in relation to the number of smaller communities work in which this kind of close community work is being done. The understanding of what the levers are, what people want from the federal government, what they want from the state or provincial government is clarified and becomes part of a consensus—that is something that empowers a larger movement.

Ihave run out of time, and I’m, in one way, relieved, because I don’t have the larger answers about recreating this larger movement, but I feel I begin to have some answers about my own society, but not as an exportable solution. One of the things you have to be able to do, which I think we really did in our Commission, is you have to understand exactly why people are taking this nativist turn—what the fears are, what the feelings are; you have to get our of your mind the epithets of “redneck” and “backward” and so on, which we simply hurl. You have to try to understand it, and then we have a way to hook the complex identities and people into a common movement, because they are complex identities.

In Quebec, for instance, we had this very bad program that wanted to deny people the right to wear the hijab. And the polls said that something like 50 percent of the population was in agreement. But then someone asked another question: Would you agree that people could be fired for wearing the hijab? And 50-something percent said No. So, people are complex, and fortunately the opponents of the legislation were hammering this point.

So, it’s a difficult and long haul, but, as I say, I’m not a pessimist. In spite of all these spirals, there are counter-spirals that are waiting to be created.

Maybe I should stop now. Thank you.

Image: Francisco Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, 1799 (detail, color overlay)