The Autobiography of Solomon Maimon

The following is an excerpt from spring 2018 fellow Paul Reitter’s translation of The Autobiography of Solomon Maimon, to be published by Princeton University Press in September 2018.

Introduction by Yitzhak Y. Melamed and Abraham P. Socher

Introduction

Midway through George Eliot’s last novel, Daniel Deronda (1876), the title character, a Jewish orphan raised as an English aristocrat, wanders into a secondhand bookshop in East London and finds “something that he wanted—namely that wonderful piece of autobiography, the life of the Polish Jew Solomon Maimon.” Eliot, who had translated those more famous Jewish heretics, Benedict Spinoza (who Maimon had read closely) and Heinrich Heine (who had read Maimon closely), left an annotated copy of Salomon Maimons Lebensgeschichte in her library.

Contemporary readers of Maimon’s autobiography included Goethe and Schiller, but it made the greatest impression on nineteenth-century Eastern European Jewish readers who had suffered a similar crisis of faith and were struggling to modernize Jewish culture or find their feet outside of it. Mordechai Aaron Guenzberg (1795-1846) and Moshe Leib Lillienblum (1843-1910) both saw Maimon as their great predecessor, the archetype of the modern Jewish heretic who had described the pathologies of traditional Jewish society and made a successful—or almost successful—break with it. Both of them patterned their own influential Hebrew autobiographies after Maimon’s Lebensgeschichte, as did the Yiddish philologist Alexander Harkavi (1863-1939), a generation later.

When the soon-to-be radical Nietzschean Zionist Micha Yosef Berdichevsky (1865-1921) left the great Yeshivah of Volozhin, in the 1880s, one of the first books he turned to was Maimon’s autobiography. Prominent German-Jewish readers included the novelist Berthold Auerbach, who based a character upon him, the pioneering historian of Hasidism Aharon Marcus (Verus), and the twentieth-century thinkers Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, Gershom Scholem, and Leo Strauss, all of whom had their first serious exposure to Maimonidean philosophy in the pages of Maimon’s autobiography. Arendt went on to list Maimon as the first modern Jewish intellectual to adopt the role of the “conscious pariah,” a role she saw as later having been taken up by Heine and Franz Kafka, among others. As an editor at Schocken, Arendt also helped bring Maimon to English readers by publishing an abridgement of an already-abridged nineteenth-century version of Maimon’s autobiography. When the Jewish loss-of-faith genre was Americanized by Chaim Potok, in The Chosen (1967), he explicitly modeled his brilliant, troubled Hasidic protagonist on Maimon. Potok had read the Schocken edition as a young man and then gone on to write a philosophy dissertation on Maimon before turning to fiction.

Historically speaking, Solomon Maimon stood at the cusp of Jewish modernity; he passed through virtually all of the spiritual and intellectual options open to European Jews at the end of the eighteenth century. Literarily speaking, he is the first to have dramatized this position and attempted to understand it—and thus himself. His autobiography is not only the first modern Jewish work of its kind, it also combines an astonishingly deep knowledge of almost every branch of Jewish literature with an acute and highly original analysis of Judaism, its political dimensions, and its intellectual horizons.

Solomon Maimon, it is generally agreed but still subject to some dispute, was born in 1753, in Sukoviborg, a small town on the tributary of the Niemen River, near the city of Mirz, in what was then the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Since Jews of that time and place did not commonly take surnames, his given name was simply Shelomo ben Yehoshua (Solomon son of Joshua). Indeed, he did not take the name of the great twelfth-century Jewish philosopher Moses ben Maim (Maimonides), until he was close to thirty years old, and studying at the liberal Gymnasium Christianem in Altona, and then only in more or less formal German contexts, although one such context was the present autobiography, with which he fully introduced himself to the literary world.

The autobiography, simply titled Salomon Maimons Lebensgeschichte, was published in Berlin in two volumes, in 1792 and 1793. It was edited by his friend Karl Philipp Moritz (1756-1793), with whom he collaborated in editing a unique journal of psychology, parapsychology, and the social sciences, Gnothi Sauton, oder Magazin zur Erfahrungsseelenkunde als ein Lesebuch für Gelehrte und Ungelehrte (roughly: “Know Thyself, or the Magazine for Empirical Psychology for the Learned and the Unlearned”). Maimon’s autobiography began as a contribution to the journal, as an anonymous case study of a Polish Jew named “Salomon ben Josua,” focusing on the social and economic arrangements under which he grew up as the grandchild of a Jewish leaseholder of the leading Polish-Lithuanian aristocrat, Prince Karol Stanislaw Radziwill (1734-1790). It was only after writing these “fragments” of his life that Maimon found himself composing an account of how, in “striving for intellectual growth . . . amidst all kinds of misery,” he had become an influential, if idiosyncratic, contributor to the philosophical literature of the German and Jewish enlightenments.

As the Autobiography’s many readers over the last two centuries will attest, it is by turns a brilliantly vivid, informative, searing, and witty, even hilarious account of his life as a Talmudic prodigy from—as he put it in a letter to Immanuel Kant—“the woods of Lithuania,” a literally preadolescent husband, an aspiring kabbalist-magician, an earnest young philosopher, a bedraggled beggar, an urbane Berlin pleasure-seeker, and, eventually, the philosopher of whom Kant would write, “None of my critics understood me and the main questions so well as Herr Maimon.” In fact, some of the incidents and encounters Maimon narrates are so entertaining and incredible that one is tempted to read his book as a picaresque novel, a Jewish Tom Jones. Yet, in virtually every instance in which it is possible to verify an incident, source a quotation, or identify a figure to whom he has coyly referred only with an initial—the drunken Polish Prince R., the charismatic “New Hasidic” preacher B. of M., the supercilious Jewish intellectual H., the censorious Chief Rabbi of Hamburg, as well as far less famous individuals—Maimon’s account checks out.

The only previous English translation of Maimon’s Lebensgeschichte appeared in 1888. The translator, a professor of Moral Psychology at McGill University named J. Clark Murray elided a few difficult passages in the first volume of the autobiography and cut the preface and ten chapters on the philosophy of Moses Maimonides with which Maimon had prefaced the second volume. He also cut the comical, puzzling allegory with which Maimon concluded his autobiography. These chapters were, Murray wrote in his preface, not “biographical” and “excite just the faintest suspicion of ‘padding.’” Although Murray’s translation has been reprinted, pared down, excerpted, and anthologized for well over a century now, Paul Reitter’s new translation is, astonishingly, the first complete accurate English translation of Maimon’s autobiography into English.

Translator’s Note

Maimon was a linguistic shape-shifter whose level of German proficiency changed according to the occasion and who was very aware of the sort of scrutiny to which his German was subjected, especially from German Jews. Indeed, one of the most famous scenes in the Autobiography involves Maimon recounting how upon reaching Berlin for the first time, his broken speech, unpolished manners, and wild gesticulations resulted in his cutting a bizarre figure, like a “starling” that “has learned to say a few words.” What breathes out of Maimon’s evocation of the scene isn’t so much resentment as an air of superiority and passive-aggressive delight. Having slyly alluded to Aristotle’s definition of man (i.e., the “talking animal”), Maimon tells of how he, the underdog, bested Markus Herz, his cultivated and thoroughly stunned Jewish partner in debate. For Maimon himself, though, the outcome should not have been surprising. While his outsider status caused him no small measure of hardship, and while the Autobiography frequently ridicules the Eastern European Jewish culture into which its author was born, Maimon was also critical of the Jewish acculturation he encountered in Berlin, seeing it as intellectually limiting. It may be in part for this reason that there can be something mocking in Maimon’s use of German colloquialisms and formal expressions. Language was the key vehicle of acculturation, and Maimon’s, as Hannah Arendt suggested, was a pariah’s acculturation. One could even say that it has elements of what other theorists would call colonial mimicry.

In the translation, I have tried to convey this. I have also tried to avoid the great temptation that attends retranslation. Or, more specifically, I have tried to avoid the temptation that attends retranslation when, as is the case here, a key text has been translated just once and without as much fidelity as one might reasonably hope for: to write in reaction to the existing translation. Whether I have succeeded, or to what degree, is of course for readers to judge.

Chapter 18: Life as a Tutor

My first job as a family tutor was an hour away from where I was living at the time. I worked for the miserable farmer I., in the even more miserable town of P., for a salary of five Polish talers. The poverty and ignorance of the population were indescribable, as was the crudeness of its lifestyle. The farmer was a man of about fifty, whose whole face was grown over with hair ending in a thick, dirty, coal-black beard. His speech was a kind of muttering, comprehensible only to the farmers with whom he had dealings every day. He not only spoke no Hebrew, but also not a word of Yiddish; he could only speak a Russian dialect, the common language of farmers in the region. Add to this scene a wife and child cut from the same cloth and also his home, which was a sooty shack, blackened inside and out, with no chimney. Instead there was just a small opening in the ceiling that served as a smoke vent. The hole was carefully closed as soon as the fire was extinguished, so that the heat wouldn’t escape.

The windows were narrow strips of pinewood laid over each other crosswise and covered with paper. The dwelling had one space: living room, drinking room, dining room, study, and bedroom all in one. Imagine, as well, that it was kept very hot, and that the wind and the dampness—ever-present in winter—would send the smoke back into the room, filling it with fumes to the point of asphyxiation. Blackened laundry and various filthy articles of clothing are hanging from rods placed along the length of the room, so that the vermin suffocate from all the smoke. Over here sausages have been strung up to dry, their fat steadily dripping down onto people’s heads. Over there are tubs of bitter cabbage and red beets (the staple of the Lithuanian diet). In a corner, the jugs filled with drinking water stand next to the dirty water. Dough is being kneaded, the cooking and baking are being done, the cow being milked, etc.

In this splendid dwelling, farmers would sit on the bare floor—you wouldn’t want to sit any higher if you didn’t want to die of smoke inhalation—and drink brandy and make a racket, while the people doing housework would sit in a corner. I would sit behind the oven with my dirty, half-naked students, translating an old and tattered Hebrew Bible into Russian-Jewish dialect. Taken together, they made up the most magnificent group in the world. It deserved to be drawn by a Hogarth, sung by a Buttler.

My readers can easily imagine how terrible this place was for me. Brandy was the only means available to help me forget my troubles. On top of all else, the Russians—who were rampaging through Prince R.’s lands at the time with an almost unimaginable brutality—had a regiment stationed in the village and neighboring areas. The house was constantly full of drunken Russians engaging in every possible act of excess. They smashed tables and benches, threw glasses and bottles at the maids’ and housekeepers’ heads, etc.

To cite a single example, a Russian was stationed as a guard in the house where I was working; he was charged with making sure that the house wasn’t plundered. One time, he came home very drunk and demanded something to eat. He was given a bowl of millet that had butter mixed into it. He pushed the bowl away and shouted: It needs more butter. A large container full of butter was brought. He shouted: Bring a second bowl of food. Another bowl was brought immediately, whereupon he dumped all the butter into the bowl and then demanded brandy. He was given a whole bottle, which he emptied into his food. Next, he called for large quantities of milk, pepper, salt, and tobacco, which he dumped in and began to devour. After he had eaten several spoonfuls, he started swinging his fists wildly. He grabbed the innkeeper’s beard and repeatedly smashed his fist into the innkeeper’s face, causing blood to gush out of the man’s mouth. After that, the Russian poured his marvelous mush down the innkeeper’s throat and raged on until he was overcome by his drunkenness, at which point he collapsed to the ground in a stupor.

Such scenes were common all over Poland. Whenever the Russian army passed through a place, they took a guide, whom they kept until the next town. Instead of having the mayor or a local magistrate choose one, they tended to grab the first person they saw. Young or old, male or female, sick or healthy—it didn’t matter, since they already knew the way from their special maps and were simply looking for another chance to brutalize people. If the person they took didn’t know the right way, they wouldn’t let themselves be steered off course. But they would beat the poor guide until he or she was half dead, just for not knowing the right way!

I, too, was once snatched up to be a guide. Even though I didn’t know the right way, I managed to guess what it was. Thus I arrived at the correct place feeling fortunate, having been punched and elbowed in the ribs many times, and also given the warning that if I led the soldiers off course they would skin me alive (something the Russians were capable of).

All the other jobs I had as a family tutor were more or less the same.

During one of them, a remarkable psychological event took place, with me as its protagonist. I will describe what happened when I reach the right point in my story. But an event of the same kind—which occurred at a different time, and which I merely witnessed—should be recounted here.

The tutor in the neighboring village was a sleepwalker. He rose one night and went to the churchyard with a volume of Jewish ritual laws in his hand. After spending a while there, he returned to his bed. The next morning, he woke up remembering nothing about what had taken place during the night. He went over to the chest where he always kept the volumes locked up, with the intention of getting out the first part, the Orach chayim (The way to life), which he read every morning. To his astonishment, only three of the four parts, bound as separate volumes, were there, the missing part being the Jore deah (Teacher of wisdom): All four had been locked safely in the chest.

Because he was aware of his condition, he looked for the missing part everywhere, until he finally searched the churchyard and found the Jore deah opened to the chapter Hilchoth Eweloth (Laws of mourning). He saw this as a bad omen, and he went home deeply disquieted. When asked why, he related what had happened, adding: “God only knows how my poor mother is doing!” He asked his employer for a horse and permission to ride to the next town, where his mother lived, so that he could find out how she was. To reach the town, he had to pass through the place where I was working as a tutor. When I saw him riding in a state of dismay—he wouldn’t dismount even for a short time—I asked him what was wrong. It was then that I heard the story I have just described.

I was struck not so much by the particular circumstances of the incident as by the general phenomenon of sleepwalking, which I hadn’t known about. The other tutor assured me, however, that sleepwalking is common, and that one shouldn’t necessarily attach a deeper meaning to it. Only the episode with the Hilcoth Eweloth chapter of the Jore deah had filled him with foreboding, he said. He rode off, and when he got to his mother’s house, he found her sitting at her loom.

She asked him why he had come. He said that he hadn’t seen her in a while and simply wanted to visit. After resting a while, he rode back without incident. But he remained uneasy and could not stop thinking about the Jore deah, Hilcoth Eweloth. Three days later, there was a fire in the town where his mother lived, and the poor woman died in the blaze. When the sleepwalker heard about the fire, he cried out in anguish over her horrible death, then rode straight to the town to see what he had foreseen.

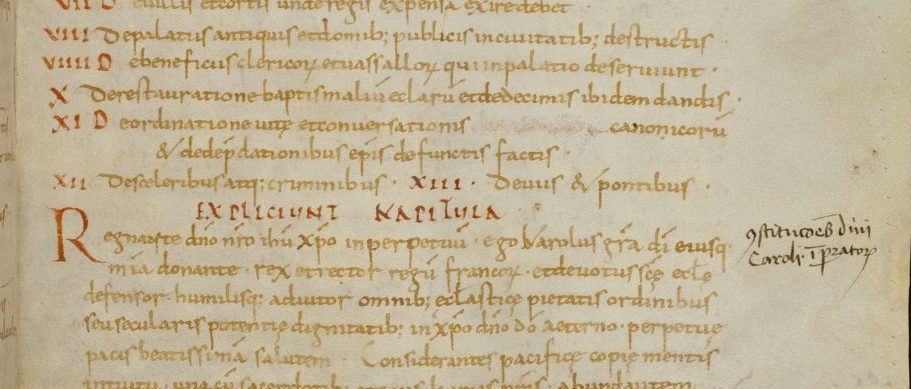

Image: William Arndt, Salomon Maimon (detail), pre-1814. Originally published in The Jewish Encyclopedia.