Trump and Transatlantic Security

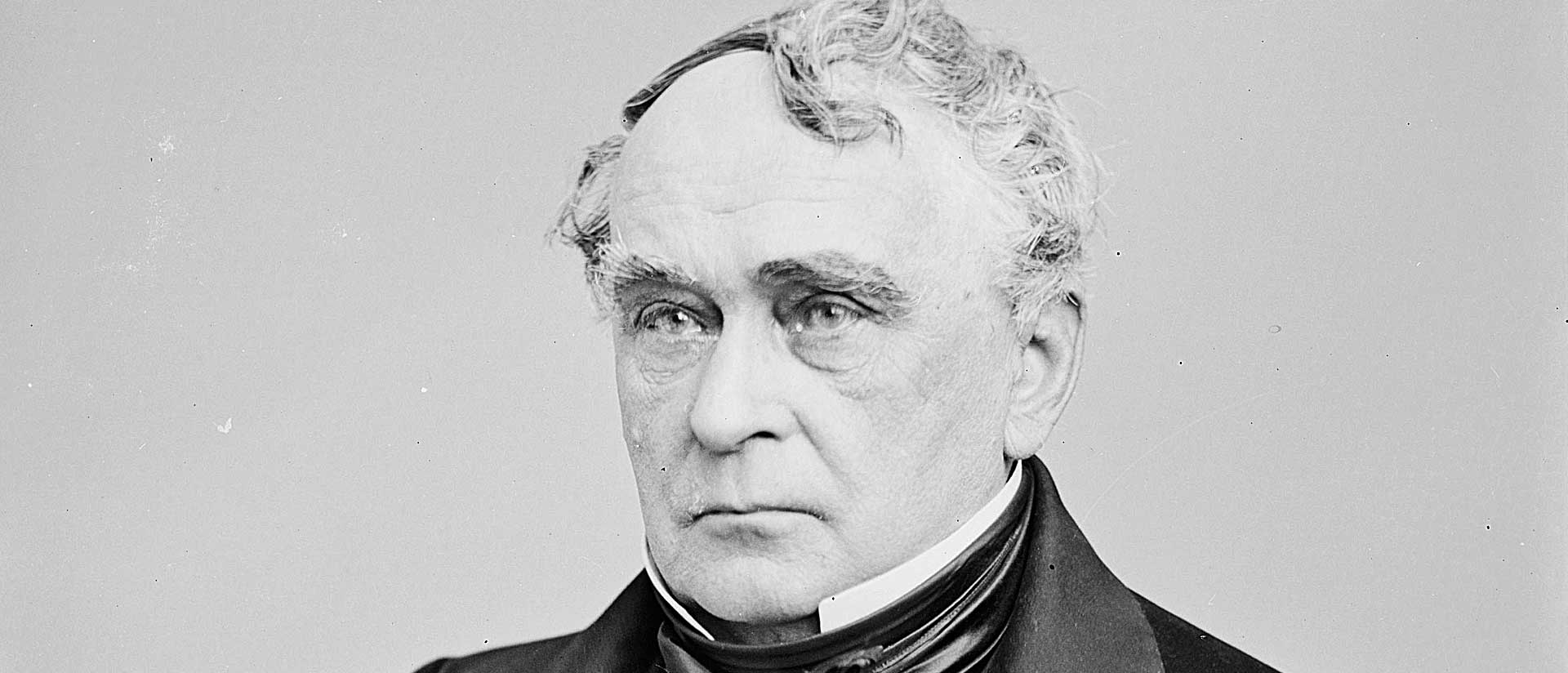

A discussion between Stephen Hadley and Christoph Heusgen

New challenges and old grievances have put the transatlantic security partnership under considerable strain in recent years. Terrorist threats, hybrid warfare, cyber security, and traditional issues such as deterrence and territorial defense dominate the agenda. At the same time, Atlanticism seems to have lost much of its political self-evidence for many observers and parts of the public since the election of President Trump. Against this backdrop, the Richard C. Holbrooke Forum brought together Stephen Hadley, former national security advisor to President George W. Bush, and Christoph Heusgen, former chief foreign-policy advisor to the German chancellor and now German ambassador to the United Nations, to discuss the challenges facing the transatlantic partnership today. The following is an edited excerpt from their June 1, 2017, discussion at the American Academy, “National Security at Risk: Order and Disorder in the Atlantic Space.”

Christoph Heusgen: When you and I worked together, back in 2005, during the second Bush administration, when one talked to someone in the White House and then to someone else in the State Department, you would more or less get the same response. It is my impression that the White House works differently now: what kind of answer you get depends on whom you talk to. Do you think this can work? How should we deal with it?

Stephen Hadley: The Trump administration has been in power less than four and a half months. It came in as a political insurgency and a populist movement that believed most of the policies over the last two decades were a mistake, and that the elites in the country had betrayed the American people. The current White House has a variety of power centers: there’s the Bannon faction, which is the keeper of the commitments of the campaign. There’s a chief-of-staff function; there’s the vice president; there’s the NSC; there’s the National Economic Council; and then there’s the family, Jared and Ivanka. Lots of different voices are speaking to this president, and he likes it; that’s clearly part of his management style.

President Trump is pretty comfortable firing people when things aren’t working. He went through three campaign teams. He’s going to throw people out until he gets a group of people that works for him. So, with the transition for this new administration, which usually takes six or eight months, it is going to take a year before we really know how it is going to operate.

Heusgen: But while they are testing things out, what happens to transatlantic relations? Are they in danger?

Hadley: I read the speech President Trump gave at NATO in Brussels, which everybody said did not reaffirm the Article 5 commitment—that an attack on one is an attack on all. Well, he spoke at an event to celebrate Article 5, and NATO’s invocation of Article 5 that was triggered after the 9/11 attack on the United States. So, the president’s appearance there, I would have thought, was by itself an indication of his support for Article 5. The fact that he didn’t say it should not raise any doubts in anybody’s mind about this administration’s and the American people’s continued commitment to NATO and to Article 5.

But I will also say that I thought your chancellor got it right. She was committed to the transatlantic relationship and to a good relationship with the United States, but that Europe needs to do more and take more responsibility for its own future. I agree with that. I think you agree with that. Donald Trump would agree with that.

My question to you, Christoph, is this: could this be an opportunity to really refocus on the aspirations of the European Union? Recommit to it and then really take it to the people of Europe and get them to recommit to it, too? The only politician in Europe I know who could do that would be Angela Merkel, and she has a potential partner in Macron.

Heusgen: There are a few things we have to do on Europe. One thing is the bureaucracy of Brussels. The Brussels institutions are doing a very good job at managing the European Union. The problem is that the people in Brussels are sometimes totally detached from reality in member states.

We have to concentrate on the issues people are most concerned about, such as security at home. We have to work so that the people in Europe feel secure. Everyone believes that the Schengen Agreement, which keeps our borders open, is fantastic, but to keep them open we have to be sure that we protect our external borders. This is a project that everybody will agree to do.

Foreign and security policy is the second issue where people also say, “Yes, there’s an advantage if Europe works together.” This is the next project we have to work on together, and the French are very open to it.

The third is economic and monetary union. We hope that President Macron will be able to do what many presidents tried but could not achieve: reforming the French economy, the French labor market, the pension system. So if Macron succeeds in putting Germany and France again at eye-level, I think that would make it much easier to convince the Germans to say, “OK, we are ready to deepen the monetary union and have a European monetary government, or something along those lines.”

Audience member: Let’s assume all the pundits are right, and leadership of the West is turning from America to Germany. What chances of success do you give them?

Hadley: I think being president of the United States is one of the toughest jobs in the world, but being chancellor of Germany is right up there with it. Chancellor Merkel will have the challenge and opportunity to try and put the future of Europe on a firm foundation. To ask her to also become the leader of the free world, on top of that, is not going to happen. It’s unfair to ask. I don’t think the apparent American step-back is going to go to the point of abdication. I may be wrong, but I don’t think it will get to the point where Angela Merkel has to lead both Europe and the free world at the same time.

Audience member: I’m interested in the supposed Russian strategy of meddling in elections and supporting populist movements. How should transatlantic partners deal with this?

Hadley: What would be a good day for Vladimir Putin? He wakes up and he learns that a fissure has opened up between the United States and Europe. He shows that the Article 5 guarantee of NATO is a paper tiger, and the EU breaks up. Russia basically signs up some sympathetic regimes in some of the central and eastern European countries and, before you know it, Russia has reestablished a sphere of influence in Central and Eastern Europe. That would be a great day for Vladimir Putin. I don’t think it will happen. The United States and Europe together are taking steps to ensure that it does not happen.

Our counterparts in Russia now say Russia is an alternative to the West. Lavrov, as foreign minister, spoke about moving into a post-Western world. I think Putin really believes he is the defender of conservative orthodoxy in the face of a declining West. That means a more problematic Russia over the long term, and managing Russia is going to be a huge challenge going forward. Neither the United States nor Europe is going to be able to do that successfully on its own. We’re going to have to do it together.

Audience member: But isn’t the real problem that some of the new US administration is thinking the same ways Russians do, with its explicitly pro-Russia policies? Isn’t that echoed in the “America first” slogan?

Hadley: I don’t know what “America first” means, and I don’t think, quite frankly, a lot of the people that use that phrase do either. Does it mean, “It’s going to be American first,” as in: I’m going to defend American interests? Well, what leading politician doesn’t tell their people they’re going to defend their country’s interests—German interests or French interests? That’s what we all say and what we all do.

President Trump talks about values, but then he steps away from standing up for freedom and democracy on the grounds that we don’t want to impose on other people’s national decisions. That’s not the United States. My worry is not the “America first” slogan; my worry is what Trump narrowly considers American interests: protecting America from attack, economic growth, and creating American jobs. Well, that is a very short-term view of American interests. It’s not the view of its interests that America had for the last 70 years, which was a more long-term and more enlightened view: working with our European allies to maintain a rules-based international order based on free markets, freedom, and democracy. We did that, at enormous cost, for seven decades, and I would argue it brought a period of unprecedented peace and prosperity. That’s the conversation I would like to have with President Trump and the people around him. That’s what I am worried is at risk. There are people around President Trump who understand that in their bones. But there are also some people around him who reject it and who talk about dismantling the international order. That’s very worrisome.

That’s one of the reasons it is terribly important for European leaders to come and talk with the administration, President Trump, and people at all levels. You know, these values matter, and this international system of rules, alliances, and institutions has kept the peace. One of the reasons we have disorder now is because that system is fraying; it’s under attack from the new authoritarians and from transnational threats like ISIS. We need to come together and create a revised and revitalized rules-based international order. That’s the conversation I think we need to be having with this new administration.

Photo: Ralph K. Penno